|

|

Abstract

Background: Interest in candida species (spp.) has been observed due to the rise and epidemiological shifts in candidiasis.

Infections with candida spp. are being seen more commonly in hospitalized patients; their emergence being favored by immunosuppression. These emerging pathogens are implicated in cases of superficial and disseminated candidiasis in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients, are often resistant to conventional antifungal therapy, and may cause severe morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients. Accurate identification of candida spp. is therefore crucial for successful clinical management and for facilitating hospital control measures.

The present study was performed to identify candida spp. in isolates obtained from oral lesions of hospitalized and non hospitalized patients with clinical signs and symptoms of oral candidiasis and to assess the possible risk factors associated with infection with such pathogens in these groups of patients.

Methods: Identification of candida spp. was performed by cornmeal agar cultures and yeast assimilation profiles using the API 20C AUX Yeast Identification System.

Results and Conclusions: Candida albicans was the most frequently isolated spp. in both groups. It was the only spp. isolated from non hospitalized patients implying either a more intense carriage of this species and/or that it is more virulent than other species. Non- albicans spp. On the other hand, were exclusively recovered from hospitalized patients. They represented 44% of isolates in this group. Five different spp. were isolated and identified as follows: C. Lusitaniae (16%), C.Tropicalis (12%), C. Parapsilosis (8%), C. Glabrata (4%), and C.Kefyr (4%). The exclusive presence of these pathogens in hospitalized patients was found to be related to a combination of 3 factors common to all patients in the group; immunosuppression, hospital environmental conditions, and selective antifungal pressure.

Introduction

The genus candida includes several species implicated in human pathology. Candida albicans is by far the most common species causing infections in humans[1]. The emergence of non-albicans candida spp. as significant pathogens has however been well recognized during the past decade[2]. Numerous records have documented the increased incidence of non-albicans spp. among hospitalized and immunosuppressed patients[3],[4], [5],[6]. Although this increased reporting may be caused by increased laboratory recognition[7], yet the emergence of these opportunistic pathogens is favored by the change in host susceptibility due to the growing number of immunocompromised individuals in the population as a result of the HIV pandemic and the use of long-term immunosuppressive therapy in cancer and organ transplant patients[1], [8].

Candida albicans and non-albicans spp. are closely related but differ from each other with respect to epidemiology, virulence characteristics, and antifungal susceptibility. All candida spp. have been shown to cause a similar spectrum of disease ranging from oral thrush to invasive disease, yet differences in disease severity and susceptibility to different antifungal agents have been reported[9]. Factors which predispose the compromised host to oral candidiasis are poorly characterized. Disease in this population represents a difficult management problem, may spread locally to involve the oropharynx and oesophagus, and is known to precede systemic infection[1],[5], [6]. Candidal oesophagitis frequently occurs in AIDS and HIV infected patients, disseminated infection however, is not as common in these patients as it is in other immunosuppressed patients[10]. Evidence suggests that some species of candida have a great propensity to cause systemic, nosocomial, and superficial infections than do other species[3].

Candida spp. identification is therefore important for successful management. Distinction between species facilitates the understanding of the epidemiology of candida spp. particularly regarding the reservoir and mode of transmission which is a requirement for the development of effective measures to prevent and control transmission of resistant pathogens[9], [11]. The aim of this study was to identify candida spp. isolated from the oral lesions of hospitalized and non hospitalized patients with oral candidiasis and to investigate the possible risk factors associated with infection in both groups.

Patients and Methods

Studied population. Specimens were collected from oral lesions of 50 adult patients having signs and symptoms compatible with oral candidiasis. All patients were recovered from Ain Shams University Hospitals. Half of the specimens were derived from hospitalized patients who were treated in different clinical departments for a variety of conditions (Radiotherapy, Dermatology, General medicine, ENT, and Geriatric Departments). Only patients in whom oral lesions occurred at least 3 days after admission were included, excluding patients who presented with oral candidiasis at or prior to hospital admission. The other half of the specimens were obtained from patients attending out-patient clinics (Endocrinology, Dermatology, and Odontology Clinics). Non hospitalized patients with remarkable health histories or underlying diseases and/or therapies known to compromise the immune system were excluded from the study. In all patients, clinical symptoms and signs of the oral disease were recorded. Oral hygiene, tobacco use, orthodontic appliances or denture wearing, and medications were noted in both groups. In hospitalized patients, medical records were examined and data on medications were collected. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors that might promote infection were recorded for each patient.

Clinical specimens and identification of isolates. Specimens from oral lesions were collected by passing a sterile cotton swab several times across the affected surface. Candida infection was diagnosed by the presence of budding yeasts with hyphae and pseudohyphae on potassium hydroxide examination. Swabs were then streaked onto Sabouraud?s dextrose agar slopes to which chloramphenicol was added (40 gm dextrose, 10 gm peptone, 15 gm agar, and 1000 ml distilled water) and incubated at 37?C for 3 days. Macroscopic (creamy moist colonies) (Fig-1) and microscopic (yeast cells, pseudohyphae, and blastospores) examination of the growths verified the diagnosis of candidiasis.

|

|

|

Fig-1: Candidal colonies

(Sabouraud׳s dextrose agar slopes) |

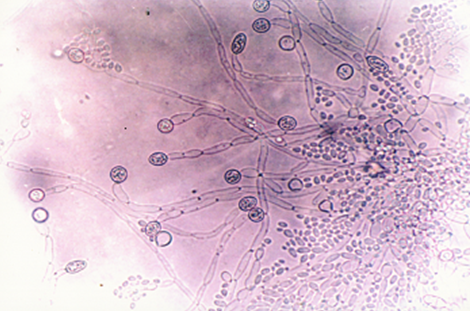

Species identification of candida isolates was performed by subculture of the obtained colonies on cornmeal agar plates and incubation at 25?C for 48-72 hours (Fig-2).

|

|

|

Fig-2: Candidal colonies (cornmeal agar plate) |

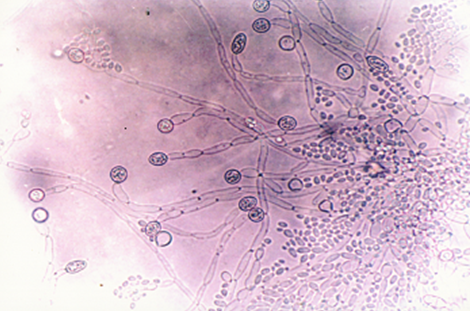

Candida albicans spp. was identified microscopically by the production of chlamydospores (Fig-3).

|

|

|

Fig-3: Candida albicans

chlamydospores |

Non-chlamydospore producing species were then identified by using the API 20C AUX Yeast Identification System (bioMérieux, France) which analyses the carbohydrate assimilation profile of each species. Each species was identified by referring to the analytical profile index provided by the manufacturer.

Statistical analysis: Differences between frequencies were analyzed by the Chi Square test (x2) and the Fisher?s exact test. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the studied patients are summarized in table-1.

|

|

Non Hospitalized

Pts |

Hospitalized Pts |

|

Number |

25 |

25 |

|

Age (years)

Mean ± SD

range |

40.2±7

(22-45) |

35.4±3

(19-65) |

|

Sex

Females

Males |

12

13 |

6

19 |

|

Source of Patients

|

Out-Patient Clinics

Endocrinology 9(36%)

Dermatology 8 (32%)

Odontology 8 (32%) |

Hospital Departments

Radiotherapy 12 (48%)

Dermatology 6 (24%)

General Medicine 3 (12%)

ENT 2 (8%)

Geriatric 2 (8%) |

|

Risk Factors

|

Poor oral hygiene

Tobacco smoking

Contraceptive pills

Non-identified (48%) |

Hematologic malignancy

Irradiation therapy

Cancer chemotherapy

Systemic antimicrobials

Systemic antifungals

Diabetes (glycosylated HB>12%)

Prolonged hospitalization |

Table-1: Clinical characteristics of the studied patients.

Poor oral hygiene, tobacco smoking, and the use of oral contraceptive pills were recorded as possible risk factors for development of the oral lesions in 52% of non hospitalized patients. In the remaining 48% of patients, no obvious predisposing factor for infection was identified. In the group of hospitalized patients, underlying medical conditions justifying admission included; hematological malignancies (48%), pemphigus vulgaris (24%), complications of uncontrolled diabetes mellitus with glycosylated HB>12% (8%), and laryngeal carcinoma (20%). Most of these patients were receiving systemic antibiotics. Other medications included cancer chemotherapy (60%), systemic corticosteroids (30%), fluconazole (11%), and irradiation therapy (14%). Poor nutritional status was observed in 70% of the patients and hospital stay ranged between 12 days and 6 months. In all hospitalized patients, oral lesions had occurred 5-7 days after hospital admission.

In all studied patients, 3 clinical presentations of candidal stomatitis were observed; pseudomembranous confluent thick creamy curd-like lesions, erythematous atrophic lesions with loss of lingual papillae, and a combination of both clinical pictures. A significant difference was found between the distributions of the 3 clinical presentations in the studied population as a whole and in both groups of hospitalized and non hospitalized patients (table-2).The pseudomembranous presentation was significantly higher than the other two presentations in all patients as a group and in hospitalized patients; where p values were <0.001 (Fisher׳s exact test). In non hospitalized patients on the other hand, the combined pseudomembranous/erythematous presentation was significantly higher than the other two presentations with p values <0.001 (Fisher׳s exact test).

|

|

Pseudo-membranous

Lesions

|

Erythematous

Lesions

|

Combined

Pseudom./ Erythematous

Lesions |

Chi Square test(x2) |

P

value |

|

All Studied

patients |

22

(44%) |

9

(18%) |

19

(38%) |

49 |

<0.001 |

|

Non Hospitalized

Patients |

8

(32%) |

4

(16%) |

13

(52%) |

50 |

<0.001 |

|

Hospitalized

Patients |

14

(56%) |

5

(20%) |

6

(24%) |

50 |

<0.001 |

Values= Number of patients (%).

Table-2: Distribution of the three clinical presentations of oral candidiasis among the studied patients.

Six Candida spp. were identified in all studied patients, with candida albicans being the most frequently isolated species (table-3). All five non-albicans spp. originated from hospitalized patients; and represented 44% of isolates in this group (table-4). All patients were infected by only one candida spp.; no multiple infections were detected.

Candida albicans spp. was significantly higher in non hospitalized patients compared to hospitalized patients (Fisher?s exact test=11.66, p<0.001). In the later group candida albicans spp. was also significantly higher than the non-albicans spp. (Fisher׳s exact test=25, p<0.001).

|

Species |

Proportion (%) |

| Candida Albicans |

78% |

| Candida Lusitaniae |

16% |

| Candida Tropicalis |

12% |

| Candida Parapsilosis |

8% |

| Candida Glabrata |

4% |

| Candida Kefyr |

4% |

Table-3: Proportions of yeast species in isolates from all studied patients.

|

Candida species |

Non Hospitalized

pts |

Hospitalized pts |

|

Candida Albicans

Spp. |

25 (100%) |

14 (56%) |

|

Non-Albicans

Spp.

|

None |

11 (44%)

C. Lusitaniae

4 (16%)

C. Tropicalis

3 (12%)

C. Parapsilosis

2 (8%)

C. Glabrata 1 (4%)

C. Kefyr 1 (4%) |

Table-4: Distribution of candida species among the two studied groups.

Distribution of Candida spp. among the three clinical presentations in the two studied groups of patients is shown in table-5.

Clinical Presentation

|

Candida Spp. |

Non Hospitalized pts

|

Hospitalized pts |

Pseudo-membranous

|

C. Albicans

C.

Non-Albicans |

8 (32%)

None |

8 (32%)

6 (24%) |

Erythematous |

C. Albicans

C.

Non-Albicans |

4 (16%)

None |

3 (12%)

2 (8%) |

Pseudom./ Erythematous |

C. Albicans

C.

Non-Albicans |

13 (52%)

None |

3 (12%)

3 (12%) |

|

Values= Number of patients (%).

Table-5: Distribution of candida isolates in clinical lesions in the two studied groups.

Discussion

According to most publications, candida albicans is the most frequently encountered species in both oral carriage and oral candidiasis[1], [12], [13]. In the present study, candida albicans and 5 other non-albicans spp. were isolated. Candida spp. identification was performed using two mycological methods applied sequentially to avoid false results and ensure accuracy. This is because misidentification of yeast species has been previously reported to result from the use of a single identification method[7]. Culture on cornmeal agar, which identifies candida albicans by chlamydospore formation, was performed initially as this was the most likely species to be isolated. The API 20C AUX system was then applied as a second step to identify non-chlamydospore forming spp. based on their carbohydrate assimilation profiles. Candida albicans was the most frequent species in the study (78% of all isolates), with a clear predominance in non hospitalized patients. In hospitalized patients, this species was also detected significantly more frequently than non-albicans spp. In this group of patients however, the proportion between albicans and non-albicans spp. was more balanced in all three clinical presentations.

Most candida infections are thought to be endogenous, acquired through prior colonization where local reduction in host resistance results in over growth of their own yeast flora[14]. The sole presence of candida albicans spp. in non hospitalized patients may therefore be related to a more intense carriage of this spp. in this group of patients. A variety of local and systemic host factors and exogenous factors have been described to increase the prevalence of candidal carriage and population levels, and enhance the transformation from the colonizing blastoconidial phase to the more virulent hyphal phase[2]. Since roughly one-third to one-half of adult individuals are reported not to carry measurable levels of candida spp. in the oral cavity, carriage perse has been suggested to be a risk factor for subsequent infection. Little is however known about the requirements for carriage or the natural barriers against carriage which result in yeast free healthy individuals[15], [16], [17]. Major systemic factors known to predispose to oral colonization and subsequent infection were excluded in the group of non hospitalized patients. Poor oral hygiene, tobacco smoking, and the use of birth control pills were regarded as factors contributing to infection in 52% of patients in this group. In the remaining 48% of patients however, apparent predisposing factors which would explain the oral infections were not identified. Candida-host interactions are a complex issue. Innate and acquired defects in neutrophil, monocyte-macrophage, B-cell, and T-cell functions are known to predispose individuals to superficial and disseminated candidiasis[3]. It has been postulated that natural barriers against yeast colonization exist at mucosal surfaces and that these barriers differ between individuals as a function of changes in host physiology leading to variation in the frequency of carriage and also the predominant species which is carried[4],[17]. It therefore seems that in this group of patients, due to an unidentified host factor, reduction of a particular barrier to colonization eventually ended in symptomatic infection. This barrier must be specific to candida albicans as this was the only species identified in the oral lesions of these patients.

The exclusive isolation of candida albicans spp. from hospitalized patients may be alternatively explained by a higher virulence of this species compared to other non-albicans yeast species. At the cellular and molecular level, studies have revealed that candida albicans is more adapted than other non-albicans spp. as an oral commensal organism[8]. This species has also been described to be the most virulent and pervasive of all candida spp.[18]. Among the various virulence factors which contribute to its pathogenicity is its increased adherence to mucosal surfaces which is shown to be a prerequisite to successful colonization and subsequent infection[19], [20]. Previous studies[19],[21] have shown interspecies variation in candidal adhesion to buccal epithelial cells, where Candida albicans demonstrated the greatest adhesion. Decreased adhesion of the non-albicans spp. has been suggested to contribute to their lower virulence and thus their limited ability to cause disease in healthy individuals[8], [19].

Oral candidiasis is widely recognized among immunocompromised patients[1], [10]. Immunosuppression was an obvious common risk factor for developing the oral lesions in all hospitalized patients. All patients in this group had developed the oral lesions at least 5 days after hospitalization and therefore their infections were considered hospital acquired according to the definition proposed by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention which states that "An infection that is not present or incubating when a patient is admitted to hospital but is detected 48-72 hours after admission is considered to a nosocomial rather than community-acquired infection[22]. It is established that compromised hosts are prone to nosocomial infections with an array of opportunistic pathogens. Numerous reports have documented an increased incidence of candida spp. among hospitalized patients[3],[4],[5],[6],[9].

Various epidemiologic factors may affect the incidence of infection with candida spp.[23]. Those species are frequently found in the hospital environment in food, air, floors, and other surfaces. They can also be found on the hands of hospital personnel[1]. Although prior colonization has been shown to precede infection in most cases of candidiasis[14], some studies[2],[9] have provided evidence that, in hospitalized patients, infection from an exogenous source, cross infection from patient-to-patient or from staff-to- patient may also be an important mechanism of transmission. It appears therefore that detection of non-albicans spp., considered to be of low virulence or "non pathogenic", in the group of hospitalized patients may be the result of both increased susceptibility due decrease in host defenses and environmental exposure to those species as a result of hospitalization. Presence of the non-albicans species in this group may have also resulted from antifungal selection pressure[11]due to the frequent use of antifungal therapy. Moreover, the wide use of systemic antibiotics might have also contributed to the promotion of the candidal oral infections.

Candidal infections in immunocompromised patients are often severe, rapidly progressive, and difficult to treat as they are associated with strains which are often resistant to conventional antifungal Therapy[2], [8],[11],[21],[23]. Identification of species and differentiation between exogenous and endogenous acquisition of infection aided by the newly developed molecular strain typing methods[24]which determine the relatedness of candida spp., is therefore important for successful clinical management and for determining appropriate control measures to prevent hospital transmission of resistant candidal pathogens.

References

1. Vazquez JA and Sobel JD (2002). Mucosal candidiasis. Infect Dis Clin North Am;16(4):793-820.

2. Fleming RV, Walsh TJ, and Anaissie EJ (2002). Emerging and less common fungal pathogens. Infect Dis Clin North Am;16(4):915-933.

3. Brawner DL and Cutler J (1989). Oral candida albicans isolates from nonhospitalized normal carriers, immunocompetent hospitalized patients, and immunocompromised patients with or without acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Clin Microbiol;27(6):1335-1340.

4. Resende JC, Franco GR, Rosa CA, et al (2004). Phenotypic and genotypic identification of candida spp. isolated from hospitalized patients. Rev Iberoam Micol;21:24-28.

5. Sanchez-Vargas LO, Ortiz-Lopez NG, Villar M, et al (2005).Point prevalence, microbiology and antifungal susceptibility patterns of oral candida isolates colonizing or infecting Mexican HIV/AIDS patients and healthy persons. Rev Iberoam Micol;22:83-92.

6. Sanchez-Vargas LO, Ortiz-Lopez NG, Villar M, et al (2005).Oral candida isolates colonizing or infecting human immunodeficiency virus-infected and healthy persons in Mexico. J Clin Microbiol;43(8):4159-4162.

7. Lo HJ, An Ho Y, and Ho M (2001). Factors accounting for misidentification of candida species. J Microbiol Immunol Infect;34:171-177.

8. Gutiérrez J, Morales P, Gonz?lez MA, et al. (2002). Candida dubliniensis, a new fungal pathogen (Review). J Basic Microbiol;42:207-227.

9. Fridkin SK and Jarvis WR (1996). Epidemiology of nosocomial fungal infections. Clin Microbiol Reviews;9(4):499-511.

10. Folly PI and Trounce JR (1970). Immunological aspects of candida infection complicating steroid and immunosuppressive therapy. Lancet;11:1112-1114.

11. Pfaller MA and YU WL (2001). Antifungal susceptibility testing. New technology and clinical applications. Infect Dis Clin North Am;15(4):1227-1261.

12. Scully C, El-Kabir M, and Samaranayake LP (1994). Candida and oral candidosis : a review. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med;5:125-157.

13. Williams DW and Lewis MAO (2000). Isolation and centification of candida from the oral cavity. Oral Dis;6:3-11.

14. Vazquez JA, Sanchez V, Dmuchowski C, et al (1993). Nosocomial acquisition of candida albicans: an epidemiological Study. J Infect Dis;168:195-201.

15. Russell C and Lay KM (1973). Natural history of candida species and yeasts in the oral cavities of infants. Arch Oral Biol;18:957- 962.

16. Odds FC (1988). Candida and candidosis: a review and bibliography. 2nd edition London: Bailliere Tindall;p.67.

17. Kleinegger CL, Lockhart SR, Vargas K, et al (1996). Frequency, intensity, species, and strains of oral candida vary as a function of host age. J Clin Microbiol;34(9):2246-2254.

18. Hannula J, Saarela M, Dogan B, et al (2000). Comparison of virulence factors of oral candida dubliniensis and candida albicans isolates in healthy people and patients with chronic candidosis. Oral Microbiol Immunol;15:238-244.

19. Ellepola ANB, Panagoda GJ, and Samaranayake LP (1999). Adhesion of oral candida species to human buccal epithelial cells following brief exposure to nystatin. Oral Microbiol Immunol;14:358-363.

20. Repentigny L, Aumont F, Bernard K, et al (2000). Characterization of binding of candida albicans to small Intestinal mucin and its role in adherence to mucosal epithelial Cells. Infect Immun;68:3172-3179.

21. Samaranayake YH and Samaranayake LP (1994). Candida krusei, biology, epidemiology, pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of an emerging pathogen. J Med Microbiol; 41:295-310.

22. Garner JS, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, et al (1988). CDC definitions for nosocomial infections. Am J Infect Control;16:128-140.

23. Lopez J, Pernot C, Aho S, et al (2001). Decrease in candida albicans strains with reduced susceptibility to fluconazole following changes in prescribing policies. J Hosp Infect;48:122- 128.

24. Lockhart SR, Pujol C, Joly S, et al (2001). Development and use of complex probes for DNA fingerprinting the infectious fungi. Med Mycol;39:1-8.

الملخص العربي

التعرف

على هوية سلالات فطر الكانديدا المعزولة من الغشاء المخاطي

للفم لدى المرضى المصابين بداء المبيضات الفموي داخل

المستشفيات و خارجها

د/ مها شاهين ، د/محمد طه

لوحظ في الآونة الأخيرة ازدياد

معدل الإصابة بالأمراض الفطرية بصفة عامة و الإصابة بعدوى

الكانديدا بصفة خاصة.

تعتبر الكانديدا البيكانز من

أكثر السلالات المسببة للأمراض الفطرية. و بالرغم من أن العديد

من الأبحاث قد تعرفت على الكانديدا البيكانز على أنها أكثر

السلالات المرضية شيوعا فقد لوحظ في العقد الأخير وجود تحول في

الإصابات بالكانديدا بسبب سلالات أخرى غير الالبيكانز و خاصة

في المرضى الذين يعانون من أمراض نقص المناعة و المرضى

المصابون بالعدوى الفطرية داخل المستشفيات.

إلى الآن لم يتم التعرف

بدقة على العوامل التي تزيد من قابلية هؤلاء المرضى للإصابة

بفطريات الغشاء المخاطي للفم و لكن بعض الشواهد ترجح أن بعض

سلالات الكانديدا عندها قابلية أكثر من الأخرى على أن تسبب

أمراض سطحية أو أمراض جهازية عامة أو عدوى بداخل المستشفيات.

لذا فان التمييز الدقيق بين هذه السلالات المختلفة يعد عامل

مهم للتعرف على الظروف الملائمة لنمو هذه الفطريات و طرق

العدوى بها مما يؤدى إلى تطوير الوسائل الفعالة للسيطرة على

العدوى بسلالات في الغالب ما تكون مقاومة لمضادات الفطريات.

لذا فقد كان الهدف الاساسى

من هذه الدراسة هو التعرف على هذه السلالات بعد عزلها من

الغشاء المخاطي للفم في مجموعتين من المرضى، المصابون بالعدوى

بداخل المستشفيات و خارجها. هذا بالإضافة إلى التعرف على

العوامل التي قد تصاحب الإصابة بالسلالات المختلفة في المرضى

من المجموعتين.

© 2006 Egyptian Dermatology

Online Journal

|